|

Art and Camille Taylor, two longtime NIOT leaders in the twin cities of Bloomington-Normal, Illinois were falsely accused of harassment by one of their neighbors and a police officer who took the call. The incident, which took place during a highly charged election season, made them realize they had to speak up. Their story and actions, and the tremendous support from their community, provide insight into implicit bias and the racism that so many people experience on a daily basis, and what’s possible when we stand up together.

Art and Camille turned a painful incident into a teachable moment (Camille calls it “serious lemonade”) and used it to launch a book drive so that all students can feel safe to be who they are.

Interview with the Taylors

Not In Our Town's Patrice O'Neill sat down and talked with Art and Camille about the incident and what happened next. Excerpts from that conversation can be read below.

|

|

Camille Taylor greets a passerby during a drive-by parade for her and her husband, Art, on July 31 outside their home in Bloomington. (Credit: Lewis Marien, The Pantagraph)

|

Patrice O’Neill: So is it fair to say that you were harassed by a neighbor?

Camille Taylor: I guess you should say that we were not given the benefit of the doubt by a neighbor who could have knocked on our door to ask if they knew anything but instead called the police. And then, the resulting incident was the police showing up at our door and again accusing us of something that we didn't do rather than asking us questions.

"The neighbor didn't ask us questions. The police didn't ask us questions. Both of them accused us of something that we didn't do and that's where the problem lies."

Patrice O’Neill: Can you start by telling us what happened?

Art Taylor: Just around the corner from our house there were individuals who parked in front of these two neighbors that live right across the street from each other. Both have Trump support signs in their yard and the individuals that parked in front of their home were playing loud music and shouting anti-Trump slogans. One of the neighbors came out and took a photograph of the car with her phone as it drove away. Upset, the neighbor’s husband decided to drive around the neighborhood and try to locate the vehicle that was captured in the photograph. Because our vehicle matched, and because when he drove around the neighborhood he saw our alternative Trump signs in our yard, he made the assumption that it just had to be us. He took a photograph of Camille's license plates and called 911.

Camille Taylor: But here's the rub though, even though the wife saw that the drivers of the car were two young white people, and he had met us and just talked to us about a month before, he ignored all that and called the police on us.

Camille Taylor: What really concerned us is he saw one of our neighbors across the street, asked if they knew whose car it was and told them that he was going to sit there and wait until the owners of the house came outside. We have no idea what would have happened, what kind of encounter we would have had with him, but he sat there and waited out in front of the house. After no one came out, he drove off.

Patrice O’Neill: Then the police came?

Camille Taylor: He (the police officer) also lied to us. He used a method that we later found out is called the sleight of hand method in questioning or accusations. He told us that he had a video of our car, perpetrating the incident. He said that on at least three or four occasions. I finally said to him, then I want to see the video. At that point, he acknowledged that he did not have a video. We got to see the body cam of the encounter (and it took) 16 minutes and 34 seconds to acknowledge something that he could have said from the very beginning: that we know that two young people were in a car that looked like yours and we're trying to find out perhaps if you've loaned your car today to some young people, or is it possible that any young people could have had access to your car? If he started off the conversation that way, we wouldn't have had any complaints with the police department at all. We would have just taken it that they were trying to follow up on a complaint from the neighbor. He took everything that the neighbor said as gospel truth, and then used that technique called sleight of hand to try to slip us up.

The chief of police, that we later met with, said that method works for 90% of the people who do bad things. So, that's why they use it. We challenged him with what about the people that don't do bad things? Don't you have any other type of techniques that you can use when you question people, particularly when it's a neighbor to neighbor complaint? He had no answer for that. That right away is a fault and a gap in our local police department in terms of their questioning techniques and how they approach the community when they're doing investigations. And so, we've made that an issue of joining along with the NAACP and other groups who are giving a list of demands to the police about reforms and our local law enforcement agencies, but that we were a prime example of how that type of approach to regular citizens causes escalation in a situation as the person is trying to defend themselves.

"Had it not been Arthur and I who had are more level headed, older, who have no nothing to hide, it could have gone sideways very fast because indeed we felt rage boiling within us, from the bottom of our toes, to the top of our head, as we had to stand there and basically give this police officer our verbal resume to try to prove to him that we were good and decent people."

And he still kept coming back with, well, we have a video, we have video, we have this on video. And then at the end, after 16 minutes, he admitted that he didn't have a video. So he lied, consistently. And that's what escalated our feelings of rage and just disbelief that someone could stand there and tell you that they had something that we knew they didn't have because our car hadn’t moved, out of that space, for 24 hours.

The real perpetrator is found

As it turned out, the guy that did the call kept looking in the neighborhood for a vehicle that matched the description and found one further down the block from where he lives, called the police again, they went to the home, spoke with the mother who admitted that it was her 17 year old daughter and a friend of hers who did the yelling and the music and all that. They were not punished at all. The officer declined to even give them a ticket or cite them for anything. And that was that.

Art Taylor: And, we have not received an apology from, from anyone, the police or the neighbor as to the case of mistaken identification of our vehicle...

Camille Taylor: ...or how we were treated.

Patrice O’Neill: And so what happened, after you stood up and called the police out?

We wrote a letter to the city council, the mayor, the city manager, the chief of police and explained the incident in detail. That letter went viral and that led to our school book drive.

The Inclusive School Book Drive

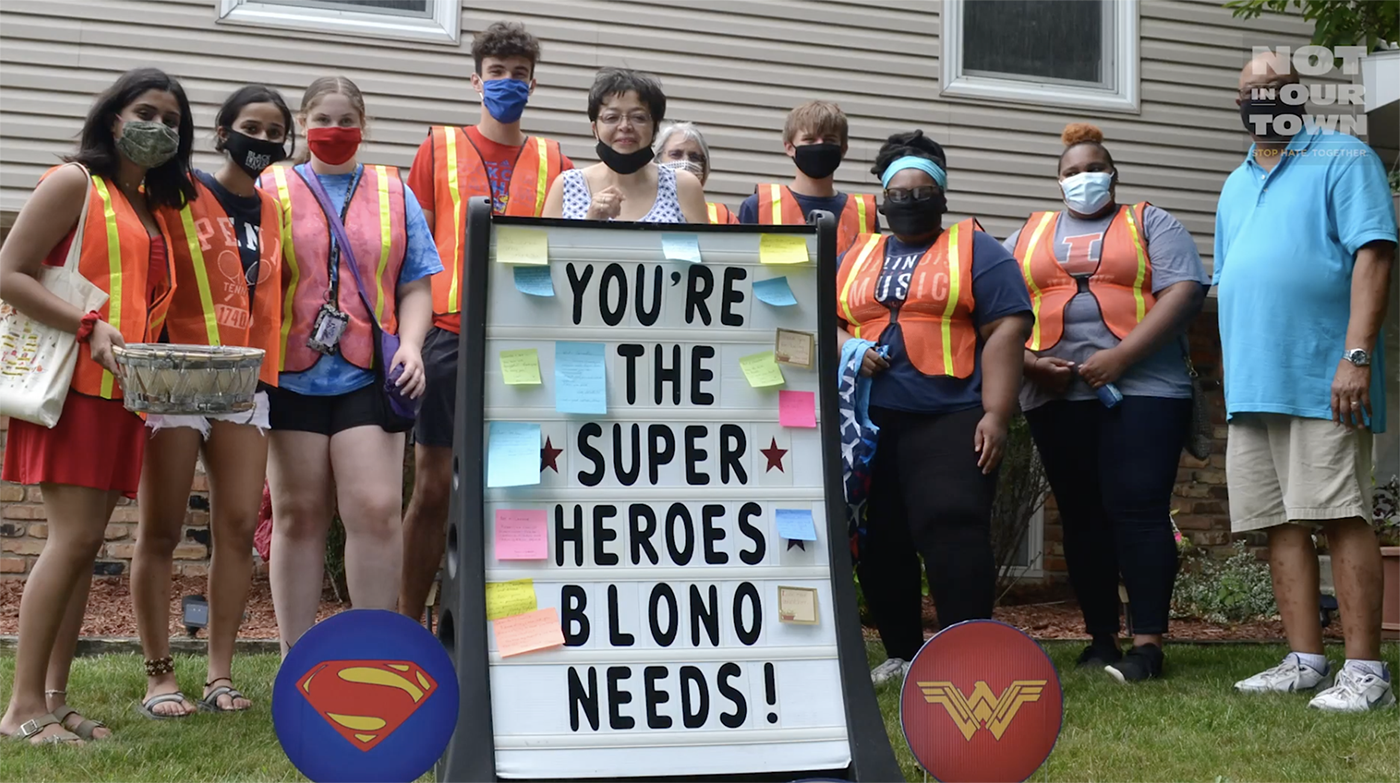

Camille Taylor: After our story went viral the community response was absolutely overwhelming. We received cards and phone calls, and our yard was filled with signs saying that we are the superheroes of Bloomington-Normal. It was just wonderful. We felt loved, we felt supported. It made us feel safe.

Art Taylor: Essentially, you can say that what occurred was that we were handed some lemons and turned them into some serious lemonade for good, that resulted in a book drive. That's the story that we like to tell.

|

|

A participant shows love during a drive-by parade for Art and Camille Taylor on Friday, July 31, 2020, in Bloomington. (Credit: Lewis Marien, The Pantagraph)

|

Mary Aplington, Camille’s co-director of the Not In Our School Program worked with the students to surprise the Taylors with letters of support and the Drive By Book Day.

|

|

Student pose with Art and Camille Taylor during a drive-by parade and book drive on Friday, July 31, 2020, in Bloomington. (Credit: NIOT Video still)

|

We have children who come in (to our libraries) and ask for different books basically dealing with self identity. For example, if you're biracial or multicultural, or you're in the LGBTQ community, or maybe your a child of divorce, or child with parents who are gay, sometimes you find no books that reflect your life experience. It's our hope that with the book drive we can fill those gaps and actually have those books in these libraries. In March, when the schools had to shut down due to COVID, our not in our school book drive came to a screeching halt.

|

|

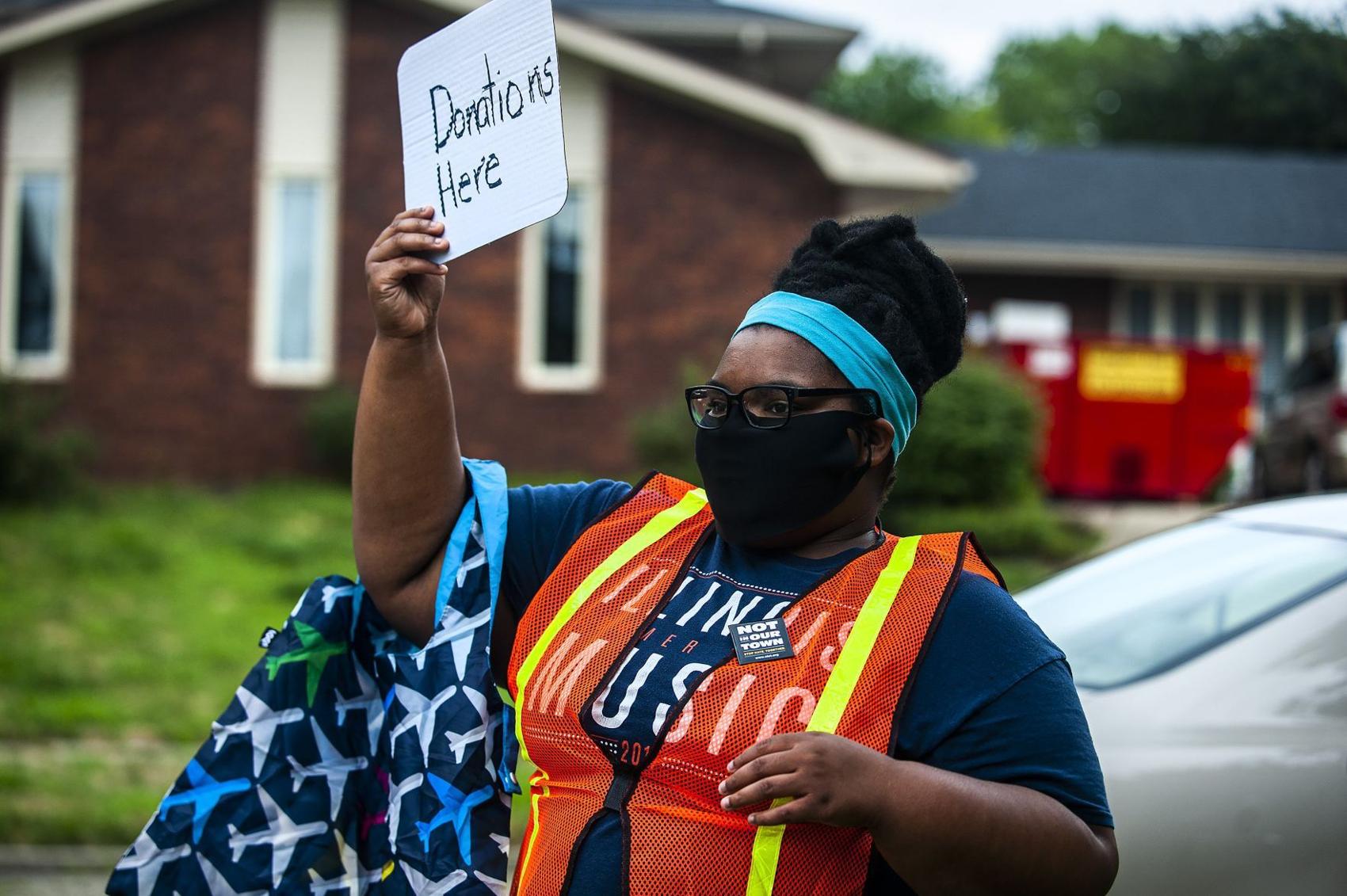

Ashyanna Watson waits to accept donations Friday, July 31, 2020, during a drive-by parade for Art Taylor and his wife, Camille, at their home in Bloomington. Donations would provide public schools resources to purchase more books normalizing diversity. (Credit: Lewis Marien, The Pantagraph)

|

Patrice O’Neill: And tell us about that. People drove by your house to express their appreciation and support?

Camille Taylor: Yes! And because people knew that we were collecting money (for the book drive) Not In Our School students stood out there with baskets and they took the money donations from people. So now we're at about $6,500.

|

Patrice O’Neill: Camille, that is really such an amazing story. In writing that letter and sharing your story, you and Art created this teachable moment in your community...

Camille Taylor: We wanted to wake up people, which is why we wrote the letter. We felt that if this type of an incident could occur to us, who have a reputation in our community for doing good things, if we could be accused of a falsehood that involved the police who basically took the side of the person who filed a false police report it can happen to anybody. We also wanted to raise awareness because people of color, undocumented people, a lot of different types of marginalized people need support within our communities. We have the privilege to be able to speak up and speak out and we took that opportunity to do so.

|

|

A participant applauds Art and Camille Taylor during a drive-by parade for the couple on Friday, July 31, 2020, in Bloomington. (Credit: Lewis Marien, The Pantagraph)

|

Not too many people can argue with the fact that we tried to turn the lemon into lemonade by seeing that we've got these books that are being purchased and the money going towards the books. We're not doing anything like counter suing them, or going by their house and making trouble. We're trying to do good in the community.

Now, everybody around here has signs up. Beautiful inclusive signs. We have black lives matter signs. We have the rainbow flags. We didn't even know that many people thought that way. We have more signs from people in their yards now than ever. And it all resulted from this incident.