|

|

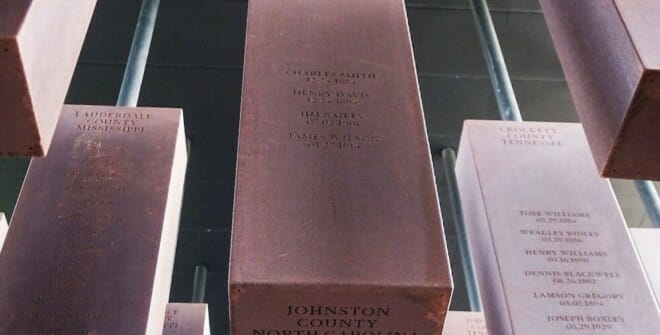

Soil from the 1878 lynching site of John Henry James joins hundreds of others at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Memorial to Peace and Justice. |

This is the journal of NIOT board member Frank Duke's participation in Charlottesville and Albemarle’s effort to memorialize John Henry James through Equal Justice Initiative’s Memorial to Peace and Justice. John Henry James was murdered 120 years ago in Albemarle County. This pilgrimage began with a soil gathering ceremony on Saturday, July 7, and ended with their return at about midnight Friday, July 13. It is reprinted from Frank's Facebook page with his permission.

|

|

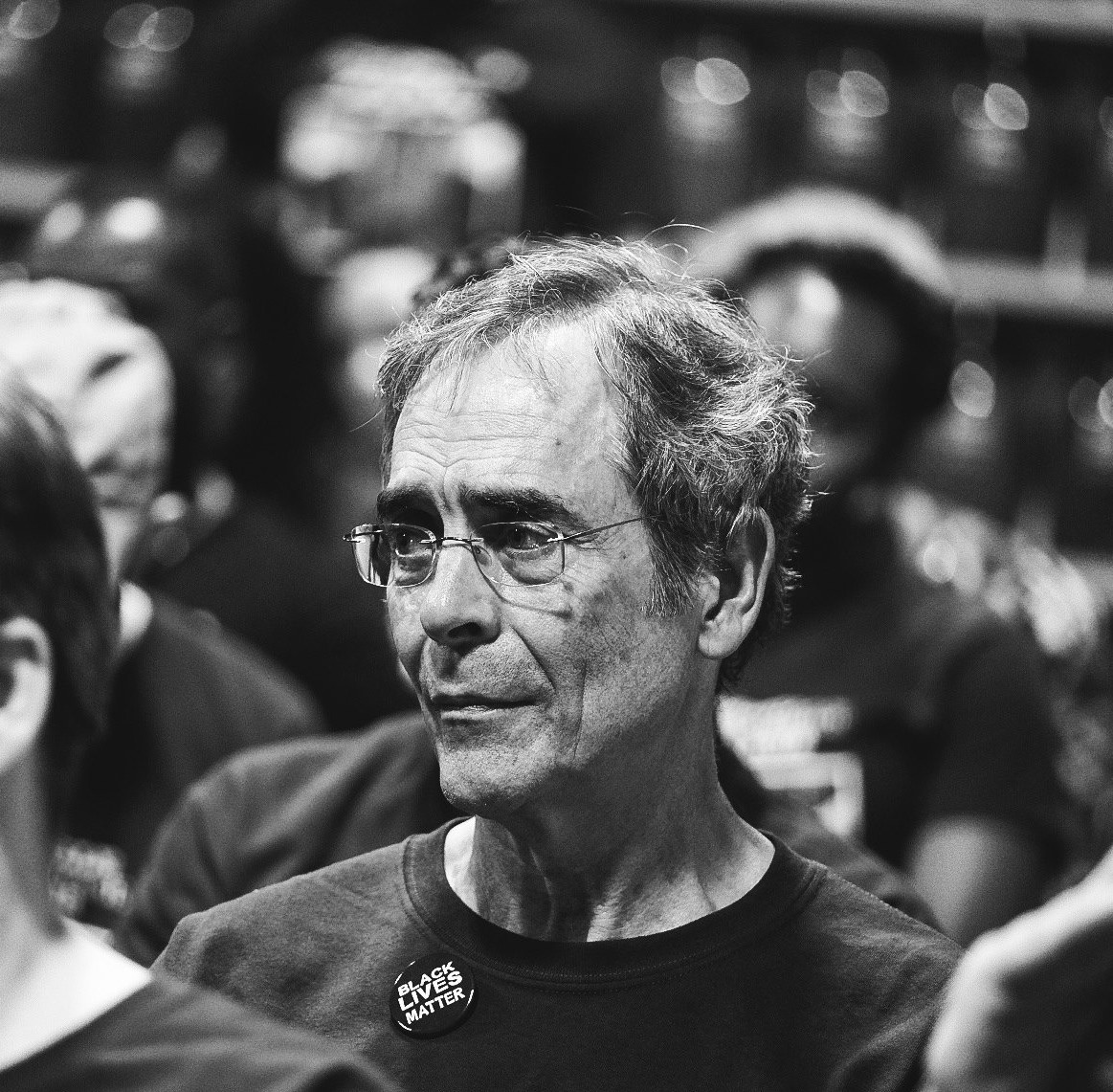

Frank Duke at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. (Photo by Eze Amos) |

I first heard of his July 12, 1898 murder of John Henry James while serving on Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials and Public Spaces in 2016. I asked – and the Commission agreed unanimously – that we include this participation in our recommendations. I had been reading On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-first Century by Sherrilyn Ifill and included a quotation of hers from that book in the Commission’s Report (this quote and Commission member Jane Smith’s research into contemporary news coverage of his lynching is available in the Report):

"...the history of racial terrorism continues to shape the relationship between and among blacks and whites in communities all over this country. If we are honest, we know that it is this history—not that of affirmative action or busing—that lurks in the dim, gray area of distrust, fear, and resentment between and among blacks and whites. It is there—where overwhelming anger, insistent denial, shame, and guilt lie—there, where our reconciliation efforts must be targeted."

C-VILLE’S Lisa Provence reported daily from the pilgrimage, with more detail and with a reporter’s skill. You may find her work here.

July 7: Gathering soil and remembering John Henry James

The ceremony of soil retrieval, open by invitation alone to a couple of dozen local residents and officials from Charlottesville and Albemarle County, took place on an unseasonably clear, cool, breezy day, with dramatic coloring of the sky and clouds. Rev. Brenda Brown-Grooms crooned a melancholy spiritual to open the reverential gathering. Dr. Jalane Schmidt, along with Dr. Andrea Douglas the moving force behind the entire memorialization process, reminded us of the brutality of what took place, the numbers of whites who participated in the murder, and the failures of the justice system to prevent the terror or to bring anyone to justice after.

Rabbi Tom Gutherz offered a beautiful Hebrew prayer, translating the many ways that names gain meaning, and concluding by naming John Henry James. He joined Rev. Brown-Grooms and Rev. Susan Minasian in a prayer of memory, inviting all gathered to intone our intentions for the present and future:

We were struggling for the possibilities for justice

We are struggling for the possibilities for justice

We will struggle for the possibilities for justice

Albemarle County Board Chair Ann Mallek notes the sadness of having spent the first 66 years of her life unaware that this lynching took place in her home community. Charlottesville Mayor Nikuyah Walker offers a powerful reminder that any public decision that does not support justice enables injustice.

Albemarle Supervisor Diantha McKeel assists Siri Russell in gathering the soil; Ms. Russell, who works for the County, is herself a descendant of a man who was lynched, which made this a particularly poignant moment. Councilor Wes Bellamy then helped student and social justice activist Zyahna Bryant gather soil in a second jar.

|

|

The six-day pilgrimage hit civil rights landmarks in Appomattox (1), Danville (2), Greensboro (3), Charlotte (4), Atlanta (5), Birmingham (6), Selma (7) and Montgomery (8). |

Later that morning Drs. Schmidt and Douglas welcomed a full house at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. Participants then were able to view the raw video of the ceremony and share the power of the words, libation, and soil gathering.

County Supervisor Rick Randolph received a spontaneous ovation for a powerful, poetic, oration detailing the litany of harm enacted upon black people by white supremacy. His speech culminated in a declaration that all citizens, residents, and immigrants legal and illegal are welcome, and he offered the County’s declaration of July 12 as John Henry James day.

The last event was a showing of the film “An Outrage.” The film explored several lynchings from the perspectives of descendants of those lynched; among other impacts was a clear demonstration of the continuing harm and pain suffered by those descendants. The film was produced by former Charlottesville resident Hannah Ayers and her husband, who explained how the film is being used to educate students from 6th grade and up about this history. They responded to questions, again emphasizing the urgency of showing the film and tying together the violence of lynching with other forms of continuing violence against black men in particular.

Sunday July 8, 2018 – Appomattox and Danville

The National Park Service site at Appomattox (#2 on map) presented a history that was complete in its battle details, but explored little of the political and social context. While the origins of the Lost Cause mythology had its beginnings earlier in the insistence that slavery was a moderating influence on Africans, harder on the whites than it was on blacks, and not a primary cause of the war, Appomattox appears to be the beginning of its embrace by the North. The story of reconciliation – the generous terms of surrender offered by Grant to Lee and his soldiers, the saluting of the defeated soldiers by Union troops commanded by Joshua Chamberlain – grew from its seeds there, accumulating other branches as its untruths became accepted in the South and the North.

This reconciliation narrative, and by implication the Lost Cause one as well, rests comfortably within the NPS site. One finds a small but packed history of black troops and African American lives a short walk away from the store where one can find the grey confederate caps, canteens, and C.S.A. belt buckles alongside their blue counterparts.

Perhaps our visit may prompt change. UVA architectural historian Louis Nelson engaged another apparent visitor about these matters, and the visitor turned out to be the site director visiting her office on her day off. Louis brought in Andrea Douglas and the director appeared not only open but eager to consider what changes may help portray a more complete history. I have photos of confederate-themed memorabilia for sale and other displays that center whiteness and share my challenges to the NPS with a reporter for a local paper.

Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History at the William T. Sutherlin house (#3 on map): Our next stop was the City of Danville, which one enters via Rt. 29 with an enormous confederate battle flag right next to the highway. The art and history museum appears as one of the homes of the wealthy – elegant, large, far uphill from the bottomland. A spread of varied desserts promises a warm welcome.

But the visit begins with a film that glorifies the former owner of the house – Mr. Sutherlin – unambiguously as a leading citizen, with no other context. Successful in anything he endeavored except keeping Virginia in the Union – he and other businessmen risked losing their fortunes in a war – he was a slave owner, a confederate officer, and a leading light in the normalcy of white supremacy. Councilor Wes Bellamy challenges that portrayal and he and others walk out.

Others disagree about the challenge, insisting that we need to understand that we are guests and we need to know the history even in its ugliness. Vice-Mayor of nearby Martinsville Chad Martin addresses the group urging people to stay for the next portion of the session. That session draws people back and with four people active in the Danville civil rights movement in 1963 and beyond – Dorothy Batson, Carolyn Wilson, Thurman Echols, and one other – provides considerable insight. Their stories matter – teachers who risked their jobs, a city employee who was suspended for a month, people who entered jail for the first time in their life.

I had to leave for a time to arrange a meeting with a Greensboro television news reporter, and when I return I find my way to the museum head, Katherine Milam, and after thanking her for the panel and the refreshments, ask if I may offer her my thoughts. I then tell her I had the same response as Wes Bellamy, that I have brought another group here before, and that I hope to do so again should they be willing to change their portrayal of their history. She acknowledges that they can do better.

I speak afterwards with fellow pilgrim and UVA architectural historian Louis Nelson, who agrees that the film needs never to be shown again. He notes that UVA has a Institute for Public History, led by Lisa Goff. Louis would also be willing to assist with the student’s and museum’s task.

So our first day of the Civil Rights Pilgrimage finds us 2 for 2 – two sites, two sites needing to change.

Monday July 9 – Greensboro and Charlotte

We embark first to Greensboro’s Beloved Community, founded and led by two people who have inspired me since I met them in 2004. Joyce and Rev. Nelson Johnson have been advocates for racial and class justice all their lives; Joyce began in high school in Richmond. She begins by walking among us while crooning a hymn, which we join. They then speak to Beloved Community’s work before showing a brief video about the Greensboro Truth and Community Reconciliation Commission. That film begins with music and singing at a “Death to the klan” rally at a public housing complex. It then turns deadly: cars carrying klan members approaching, a confrontation with shouting and what looks like people hitting one another with fists and signs, and then - the klan coolly getting rifles from their car trunk and shooting at the demonstrators. 5 lay dead, 10 wounded. 5 human beings. One a young, black, female student; two Jewish men; one Latino; and one white man. All dead.

|

| A stop on the journey in Greensboro's Beloved Community. |

The narrative that emerged is familiar to Charlottesville: a shootout between two bad groups. Two trials with all-white juries found no guilt despite film evidence. A civil suit did find some of the klan and the city’s police department liable for damages, but their finding did not change the narrative.

So things stood until the early 2000’s, when the Johnsons and others succeeded in convening the U.S.’s first Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The City Council split exactly on racial lines in voting against endorsing the Commission, which nonetheless spent two years examining evidence, hearing testimony, and deliberating findings and recommendations.

The Johnsons spoke powerfully about the Commission, about the moral basis for their work, about how they work to make change. A number of people on the pilgrimage noted the parallels between their experiences and ours. Nelson Johnson spoke of the need to seek the humanity that he believes must exist in everyone. They refuse to adopt the tools of the oppressors; they live by nonviolence. Their nonviolence is not passivity; it is robust, it insists on truth, and it demands justice. Our group probed for guidance long past the scheduled time for ending, finally offering an ovation before Joyce Johnson closed our time together with a song.

I spoke again to a local TV station, emphasizing again the core message: we keep repeating the worst of our history – the racial violence - in part because we do not learn our history.

Our false histories, represented in books as well as our public spaces, cause real harm. Once we bring back the memorial to John Henry James, nobody will be able to deny that portion of our history.

We then walked to the Greensboro Civil Rights Museum, the former Woolworth building made famous by the first sit-ins at lunch counters. It was four male freshmen students who, after spending a long time deciding whether and how they would protest, ignited the sit-ins that swept across the South. Eventually they were joined by other students and even high school students.

I had always associated the assaults against those leading these counter sit-ins, made famous through news films, with Greensboro, but in fact that happened elsewhere. The police chief refused to arrest them, saying that they had broken no laws – which of course did not stop other locales from imprisoning civil rights activists. And because their nonviolence were relentless in their pursuit of integration, they won.

We then drove to the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte. K(NO)W Justice K(NO)W Peace is a community-created exhibit their about police shootings with many interview of the Charlotte killing of Keith Lamont Scott. So many killings.

Because we extended our stay at Beloved Community we had barely an hour, but the stories of Charlotte residents told a too-familiar history very well. We drove on to Atlanta by way of a late dinner in Greenville, arriving near midnight.

Tuesday July 10 - The King Center in Atlanta

“Bus Twooooo!” has become our calling-in, thanks to DeTeasha Gathers (pictured, right). She is our spirit guide, along with her duties as bus coordinator.

|

|

Andrea Douglas, one of the two organziers of the trip. |

Our day in Atlanta begins with a visit to the King Center, where Atlanta City Councilor Amir Farokhi greets and flatters us by stating how they and others are looking to Charlottesville’s example in the fight for racial equity and against white supremacy. We are joined by former Charlottesville resident Donell Woodson, who serves as our guide for most of the day. We also visit Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King’s father pastored for decades – the church that helped bring him up. As is the case throughout the trip, our pilgrims penetrate through the standard patter of presenters and ask hard questions; we seek truths.

We walk from there to the King Historical Park, where Coretta Scott King was laid to rest in 2006 alongside MLK, Jr. Linda is approached by two tourists from Indiana, who like – and seem surprised at - her Black Lives Matter button. This happens frequently on this trip, as it does sometimes at home. We take photos of them and their children and wish one another well, pilgrims all. We have little extra time but make our way through the gift shop; many of us on this trip return with new shirts, hats, stickers, books, and other paraphernalia.

The day has turned hot and we have been outside, and a few of us need some relief, so while some go into the home that served as the King family home until MLK, Jr was about 12, others find water and shade. We hear of his best friend, a Polish boy, who soon enough was told that he could not play with “Michael” (his given name until his parents changed it to Martin) because of his race. The demon of racial hierarchy is never far away, even in this multi-racial city and multi-racial neighborhood.

We then walk to a restaurant in the Sweet Auburn district, where we are fascinated by the work of the Historic District Development Corporation; our guide Donell Woodson serves on their Board. Their story of how they have preserved affordability and the character of the largely black neighborhood while building new homes inspires us. We wonder how we might bring this back to Charlottesville and pepper the staff leadership with questions, which they answer graciously.

We conclude our programming by walking to the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. This museum placed racial civil rights within the broader context of global human rights, which I appreciated. I find their selection of tyrants an odd one with what seems like haphazard selections from Chairman Mao to Idi Amin. But that was the only false note of the day.

I almost miss the most powerful museum exhibit of the entire trip, but get to it just before closing. This is a reconstructed lunch counter of the type at the center of the sit-ins. One dons headphones, closes eyes, places hands on the counter, and then is transported – through sounds of racial taunting that appear to move through space and shaking of the seat – into the 1960s. Some of us cannot last the entire two minutes of this trial, and others are shaken. I envision my mother confronting the Nazi ideology that kicked her out of two schools and prevented her completing her education, and her brother my uncle suffering imprisonment in the concentration camp Hinzert, and tell myself that I can certainly endure a simulation. Which I do.

|

|

Miriam DaSilva experiences what it was like to sit-in at a segregated lunch counter. (Photo by Eze Amos). |

Wednesday July 11 — Birmingham, Greensboro and Selma

We begin the day with a somber visit to Birmingham’s 16th St Baptist Church. This is the infamous site of the Sept. 1963 bombing by a known KKK bomber that killed four beautiful little girls and seriously wounded the sister of one of the girls. Killed for attending Sunday School. The church has become a memorial, recently receiving support from the National Park Service. Along with other sites it also has recently been nominated for World Heritage Site status.

We spend time in the sanctuary hearing from a long-time member of the church. We watch a short film detailing the history of the bombings and the long, often abandoned prosecution of those who plotted and planted the bomb. We spend a good bit of time with questions and are joined by an elder who adds depth and another, more critical perspective of Birmingham’s present. Our questions are also deep, concluding with Mayor Walker’s probing of the extent of prosperity and poverty within the black community. The first gentleman believes that Birmingham’s progress has left them somewhat better than other communities, with a thriving black middle class and black mayor, police chief, and fire chief; the other does not disagree, but describes in more detail the continuing racial disparities in education, employment, health, and more. Many of us make a real connection with both, and the latter accompanies us to the International Civil Rights Museum and then lunch, and then drives to Montgomery for the next day’s activities.

The 16th Street Church is cross-corner from where the infamous police dogs and fire hoses of Bull Conner were turned on the children who left their schools to undergo mass arrests. Kelly Ingram Park has been turned into an urban park with various iconic figures – statues of firehose nozzles, growling dogs, police, and the children. That in turn is just across from the International Civil Rights Center and Museum. Another short film introduces us to the march to voting rights in Alabama and, eventually, the country. The screen then opens to various displays of related history – busing, voting rights, and more. We are on our own to view the many displays and videos.

In the meantime, a few people ask the organizers whether we could also go to Selma, which is not on our schedule. Some do not want to take the time and one suggests that one bus could go directly to the hotel in Montgomery and the other to Selma. I am on the side of the Selma trip and show that it will add no more than two hours. Andrea issues the final edict: this is a civil rights pilgrimage and we will not miss the opportunity to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. So off to Selma we go.

|

|

In Selma, side-by-side memorials to the “Unknown Soldier” and “Unknown Slaves.” |

In Selma we approach the bridge with reverence; because one of the two buses got lost, we are a smaller, more intimate group. We walk across the bridge not singing but lost in our own thoughts. Mine include the realization that I have not yet earned the right to cross that bridge in the footsteps of those whose lives were at risk in 1965, who suffered such brutality (50 were injured in the first of the three efforts on Bloody Sunday, March 7). And crossing this bridge on our way to memorialize the lynching of John Henry James, I recall the many lynchings held on similar bridges – public spectacles all, of course, and often captured in photos with the dangling bodies belying the calm river below.

There are five medium-size monuments to the leaders of the voting and other civil rights efforts on the Montgomery side of the bridge. A newly installed historic marker from the Equal Justice Initiative documents several lynchings in the Selma area; our first view of what is similar to what we will be bringing home adds to the solemnity of the occasion. A newer, informal installation attracts us in groups of two and three: side-by-side memorials to the “Unknown Soldier” and “Unknown Slaves”. Their folk-like, carefully crafted symbols include a boat to bring their souls back to Africa and other African art. Hanging nearby is a solemn reminder: a short noose.

We return to the bus to be invited by (Deacon at First Baptist Church) Don Gathers to join him on the bridge in prayer. Some 20 of us crowd onto a wooden structure at the bridge. As we join hands I feel compelled to kneel as first Don, then others add their prayers for guidance, prayers of thanks, and prayers of remembrance. We embrace in tears at the power of loss and resilience displayed and remembered here.

We hear from the delayed Bus 1 a complaint on WhatsApp that we should have experienced this visit to Selma together. Don replies that we are and have been together, and the separation of our buses will not stop that.

We arrive in Montgomery at 8 pm and find that our intended restaurant, Martha’s Place, was unprepared for us and closes at 8; however, they remain open and offer us a delicious and filling soul food buffet. Martha’s is the best! And it is our final event before reaching Montgomery at last.

Thursday July 12 – Montgomery, Alabama

Today is John Henry James day. We remind one another of this throughout the day, repeating his name collectively and individually.

We begin at the Civil Rights Memorial Center of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). Again, we are confronted with the violence of white supremacy, the incredible bravery and resilience of ordinary black people, and the sacrifices of the African Americans and the smaller group of whites who came from outside the south to support the civil rights movement. We are reminded of the sacrifice of Heather Heyer by the memorial photo that is in one of the halls of martyrs. Susan Bro patiently explains to our group and others who happen to be in the Center how she appreciates that SPLC “got it right” – that Heather was not a leader, but an ordinary person who wanted to support the movement.

The Center also has a room with a wall devoted to names of supporters, where you may indicate your willingness to join the fight for racial justice and see your name appear scrolling down the wall alongside others. In this room, SPLC has added two special images for our visit; the left memorializing Heather, the right showing the photo of the memorial service held in Charlottesville High School’s Martin Luther King, Jr. auditorium, along with the language from her eulogy that resonated so strongly with our community and the whole country: “They tried to kill my daughter to shut her up. Well guess what – you just magnified her.”

We then walk the few blocks to Dexter Baptist Church. I marvel at a state where a black church may be located a stone’s throw from the capitol even as those running the state worked to remove every right from the members of that church.

We are greeted by a virtuoso piano player, who turns out not to be a church member but instead our fellow pilgrim and 15-year-old Dante Walker. That sets the tone for our visit, as our hostess is a fireball – she soon has us chanting, singing, cheering, and fully enraptured by her presence. She makes a connection by her confession that she twice felt drawn to suicide, before accepting that her voice (and it is powerful!) is a gift from God that she will not waste.

She asks some of us to answer questions – to the pianist, where MLK’s “I have a dream” speech took place (he hesitated but correctly identified Washington, DC); to me (heart in throat), where he was standing when he made that speech (my quick and correct answer of the Lincoln Memorial did not reflect my own moment of doubt), and, stumping our mayor (and most of us, including me) the title of the speech King gave on April 3, 1968 (“I have been to the mountaintop”). We hear of King’s journey as pastor of Dexter – his first and only pastorate – and are reminded that Vernon Johns, uncle of Virginia’s Barbara Johns who led the famous Moton School lockout, preceded him in that role. She draws laughter as she relates that Rev. Johns was loved by the church, but he pushed his congregation of mostly black professionals to understand that their sisters and brothers who did not have their fortune needed their active support.

Apparently the congregational leadership called Dr. King with some relief when Johns left, thinking that as a new, younger minister he would engage less in political activities. Johns would place the titles of his sermons in front of the church – Dexter only one block away from the Capitol building – titles mentioning the murder and rapes of whites against blacks. When the police leadership called him in to ask why he would stir up trouble like that, he invited them to attend – an invitation they did not accept.

We all traipse downstairs to the church basement, which serves as a museum as well as church offices. A large mural painted by a long-time member depicts highlights of the civil rights movement. Our guide continues to hold court, and when we finally part she grabs each of us in a warm embrace, takes a selfie or two, and leaves us feeling both educated and loved.

And now after returning to the hotel for a quick boxed lunch, we drive the few blocks to the Equal Justice Initiative offices to complete this trip’s mission. We have been joined by several others – City Councillor Cathy Galvin, County Board of Supervisors Diantha McKeel and Ned Galloway, County staff Siri Russell, whose ancestor was featured in the Outrage film we saw earlier, and 5th district congressional candidate Leslie Cockburn, all of whom flew in for this event.

We are greeted by a number of staff and make our way into an auditorium, which we fill. We stare at the back wall, filled with jars with the soil taken from the sites of lynched African Americans - in Alabama alone.

We are greeted by EJI founder Bryan Stevenson. He speaks for 10 minutes without notes, weaving in stories from his book Just Mercy and talking about how important our work is in Charlottesville. He is informed, persuasive, and mesmerizing with his call to tell the truths of our founding that we have been afraid to talk about – at least the we that is white.

Councilor Wes Bellamy publicly thanks Stevenson for his visit in 2016 when Bellamy asked him whether it made sense to take down Confederate statues, and Stevenson’s affirmation then. We then begin the ceremony whose purpose brought us to Montgomery: to honor John Henry James by bringing the soil from the site of his lynching to the memorial. Andrea Douglas speaks first, with passion and power, of the meaning of this pilgrimage, fully matching the inspiration of Stevenson. She honors her co-leader Dr. Jalane Schmidt, her new sister, and extends that honor to all who have gathered. We then repeat the ceremony that we followed when we gathered the soil back in Albemarle County: Jalane reminds us of the brutality of what took place, Rabbi Tom Gutherz offers a Hebrew prayer, translating the many ways that names gain meaning, and he and Rev. Brenda Brown-Groom and Rev. Susan Minasian lead a prayer of memory, inviting all gathered to intone our intentions for the present and future:

We were struggling for the possibilities for justice

We are struggling for the possibilities for justice

We will struggle for the possibilities for justice

We then are each invited to transfer the soil from the jar we brought to the jar that EJI will store. One at a time we do so. Some of us wish we could have done this in silence; the chattering seems out of place in the solemnity of the moment.

|

|

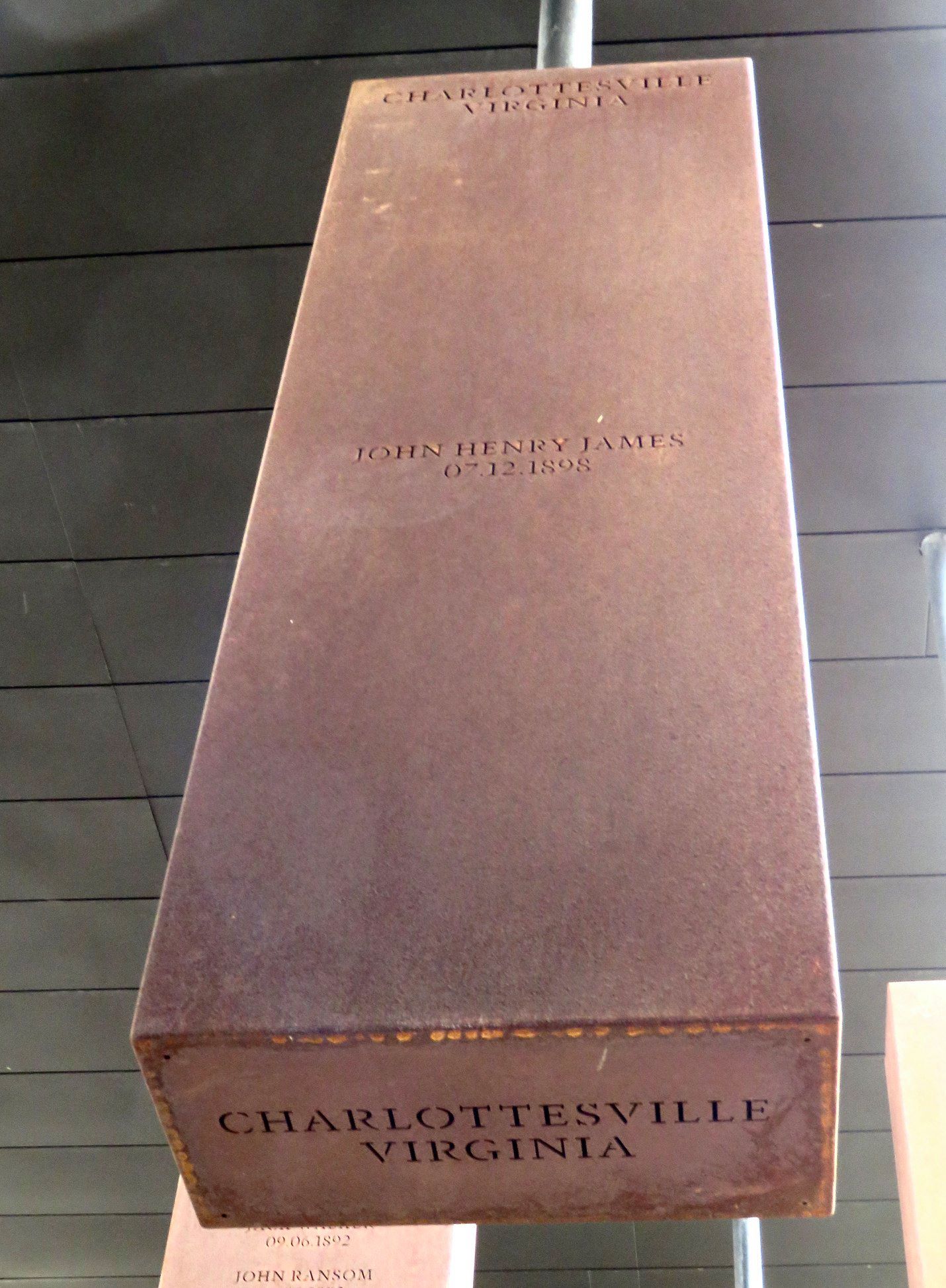

John Henry James memorial at EJI Memorial to Peace and Justice. |

It is past time to visit the Memorial to Peace and Justice itself. I have been looking forward to this since I first heard of its design some 18 months earlier. I admire the sheer brilliance and ambition of this memorial – each community invited to examine its past, and those stained by the racial terror of lynchings to collect the soil from their lynching’s site and bring it to Montgomery. In return, we may bring back the coffin-like structures with the name of the county and name or names of victims engraved. Each community will have its own reminder of this history. At the same time, visitors to the Montgomery memorial will be able to see which communities have done this work and which have not; the coffin shapes are laid together on the ground, organized by state. Virginia’s line of shame is far too big, but even then is dwarfed by those of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.

The iconic images of the memorial most have seen are part of the permanent structure: hanging from ceilings and open to the outdoors, hundreds of the coffin structures drop lengthwise. We quickly find that of John Henry James. It is one of the first that can be seen as you climb the path and enter the memorial, but 10 feet or so away from a railing that prevents a closer view. The lettering is difficult to see, particularly the letters John Henry James, and rather than Albemarle it lists Charlottesville as the location. Some pilgrims have already made their way to a lower level to view it from below. The bottom also has Charlottesville inscribed on it, but nothing else – the box is gray, metallic, aged (despite having been dedicated mere months earlier), and sad.

Unlike every other site of this pilgrimage, and to my surprise, I remain largely unmoved by this memorial. The exceptions are the counties with multiple lynchings, including some where more than one family member is murdered on the same day. Despite myself I find the memorial too sterile; despite the names, I find it impersonal. I wonder if it is because of the crowds, wandering as though this were any other exhibition? I know and am relieved that my response is not the experience of others, and perhaps mine will change over time. I want to visit at another time.

Our planned day ended with a final visit to the EJI offices, where a staffer moderated a panel with Mayor Walker and Drs. Douglas and Schmidt. My key takeaways in a panel tht has many may be summarized by Andrea's statement:

Andrea: “When my past is no longer my present, then I will be ready to move on.”

And so ends our pilgrimage, with only the long drive home to complete our travels. Or more accurately, so ends this portion of our quest. We know we will return to the same community we left, with its vast beauty and deep ugliness, its remembered history and its forgotten, its rights and its piercing wrongs. Our real work is just beginning, as the work of justice and equity is always being renewed. The moral arc of the universe is long, and it only bends the direction we make it bend. In the name of John Henry James and many others, let us make it bend towards justice.