Seventy-five years ago, nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes, their jobs, their schools and their livelihoods to live in armed camps during World War II. The feature-length documentary film And Then They Came for Us brings this history into the present, retelling this difficult story and following Japanese-American activists as they speak out against the Muslim registry and travel ban. Featuring George Takei and many others who were incarcerated, as well as newly rediscovered photographs by Dorothea Lange, the film offers interviews with former detainees.

|

|

Woodland, California. Filled with evacuees of Japanese ancestry, the special train is ready to depart from this rich agricultural section for the Merced Assembly Center, 125 miles away. (Photo by Dorothea Lange, May 20, 1942) |

Actor and activist George Takei, who at the age of seven was forced with his family from his home in California, wrote movingly about the "parallels between what once happened and today" in The New York Times:

"It is imperative, in today’s toxic political environment, to acknowledge a hard truth: The horror of the internment lay in the racial animus the government itself propagated. It whipped up hatred and fear toward an entire group of people based solely on our ancestry. ...

If this seems a practice only of years long past, consider that today we need merely replace “Japanese-Americans” with “Muslims” for the parallels to emerge. Once again, we are told by our government that a blanket ban is needed. So brazen is this same troubling logic that a Trump surrogate even cited Japanese-American internment as a precedent for the Muslim ban. Both rely upon the presupposition of guilt, one by race, the other by religion. Most chilling of all, both arise out of government policy and action."

Knowing our history is the first step to ensuring we do not repeat it.

And Then They Came for Us, directed by Abby Ginzberg and Ken Schneider, is a cautionary and inspiring tale for these dark times. In addition to telling the story of what happened to those Japanese Americans who peacefully complied with evacuation orders, the film also tells the story of Fred Korematsu, who sued the US government over the forced evacuation but lost, in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. It took him 40 years to finally get justice in his case.

We talked with filmmaker Abby Ginzberg to learn more about the film and why it's so important for Americans to remember this part of our history now and what we can do to make sure it doesn't happen again. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

NIOT: Why did you decide to make “And then they came for us”?

Abby Ginzberg: I was approached by someone who was helping to fund the publication of the new book of Dorothea Lange's photographs of the incarceration called Un-American: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II (by Richard Cahan and Michael Williams). He thought a documentary would be a good companion piece for the book. Initially, I did not want to do a film about a book, but after reviewing these amazing photographs that had not been seen before — at the same time that the Trump administration started to promote the Muslim travel ban — I saw a need for a film that connected what we did to Japanese Americans during the war and what was happening right now in the country. I conceptualized the film as one that would link these two episodes together and we began to work on it by interviewing people documented in the photos as children.

How many Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes during WWII and how long was their period of internment?

Ginzberg: 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to camps. The length of time varied depending on the circumstances of the family and the camp. Satsuki Ina, who is featured in the film and whose father was identified as a "dissident" was born in Tule Lake camp and her family spent over four years incarcerated there. Other families spent between one and three years in the camps.

The film shows numerous photos taken by photographers Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and others, many of which were commissioned by the US government. Can you talk a little bit about these photos and the struggles between the photographers and the government about what could be photographed. What was the government trying to achieve with these photos?

Ginzberg: Dorothea Lange was hired by the US government to document the forced removal of the families to show that it was "orderly" and that "there was nothing to complain about," according to Elizabeth Partridge, her biographer. In addition, there was some indication that the government was documenting the incarceration in case US soldiers became prisoners of war in Japan, so we would have some leverage for negotiating their treatment.

There were several other photographers — Clem Albers, Francis Stewart, Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and Charles Mace — who were also hired by the government, but Ansel Adams was not. He was a friend of the administrator at Manzanar [Camp] and he was invited to photograph there based on this friendship. Dorothea's and the other government photos went to the National Archives where they are in the public domain. Ansel Adams donated his photos to the Library of Congress and they are not part of the official governmental record, but are also available to the public.

In the Dorothea Lange photos of what the government euphemistically called the “evacuation,” it struck me that so many of the people headed to the internment camps were wearing their Sunday best. They are all so dressed up. Why was that?

Ginzberg: Here is what Dorothea Lange wrote about it:

"These people came with all their luggage, and their best clothes, and their children dressed as if they were going to an important event. New clothes. That was characteristic."

What I would add is that people had no idea where they were going and when they arrived at race tracks and were placed in smelly barracks from which the horses had just been removed, they were shocked. Many families spent months at the Tanforan and Santa Anita race tracks before being sent to the camps. At the time of the forced removal the camps had not yet been built, so people were first sent to race tracks and other holding facilities.

|

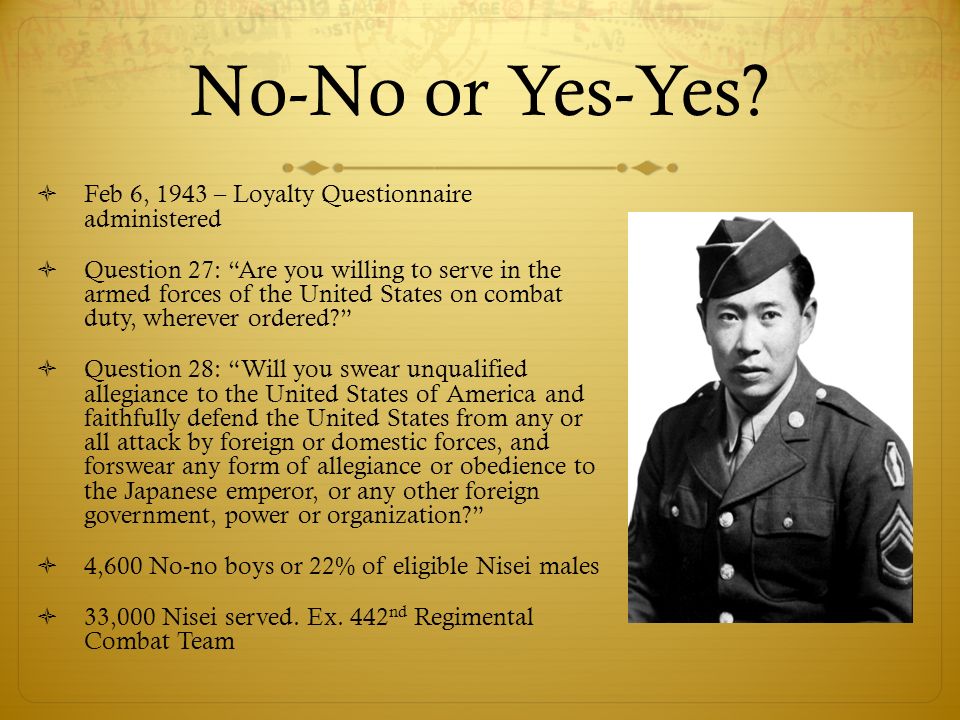

What was the loyalty questionnaire and how was it used to punish people?

Ginzberg: In 1943, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) joined forces to create a bureaucratic means of assessing the loyalty of those incarcerated in the camps. All adults were asked to answer questions on a form that become known informally as the "loyalty questionnaire." The registration program provoked a wide range of resistance due to its provocative "loyalty" questions and built resentment among many over their unconstitutional wartime treatment.

Questions 27 and 28 were particularly problematic. Question 27 asked if Nisei men (those born in the US) were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as serving in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. Question 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

Both questions caused a great deal of concern and unrest. Citizens resented being asked to renounce their loyalty to the Emperor of Japan when as Saburo Masada says in the film, "we didn't even know who the emperor was so why are they asking us that?" If you answered either or both questions, "No,' you were considered disloyal and were sent to Tule Lake camp, where additional restrictions and hardships were the order of the day, and where people were placed in a "stockade" or prison within a prison.

It took Fred Korematsu over 40 years to get his conviction vacated, but the Supreme Court case that he lost, which held that compulsory exclusion was justified during circumstances of “emergency and peril,” has not been overturned, even though documents have come to light showing that the government lied about the security risks at the time. As the Supreme Court considers the Trump administration’s travel ban, should we be concerned? Are recent events are setting off alarm bells for Japanese Americans who lived through World War II?

Ginzberg: As Fred's daughter, Karen Korematsu correctly states in the film, the Korematsu case decided by the US Supreme Court in 1944, is still Supreme Court precedent, in spite of the fact that the ruling itself has been discredited.

The challenge to the Muslim travel ban case was argued at the US Supreme Court in late April, and will be decided by the end of June. The children of Korematsu, Yasui and Hirabayashi, the three people who were found to have violated the WW II orders of incarceration, filed an amicus brief in that case arguing that their parents' incarceration was based on false representations to the US Supreme Court by government officials, alleging that all Japanese Americans posed a security risk to the country. In their brief they urged the Court to reject the government's similar claim that all Muslims from the six identified countries pose a threat to national security.

As actor and activist George Takei says, "we are seeing the same sweeping generalizations being used against a minority based on their race and religion that we once saw being used against Japanese Americans." This led him to get 300,000 people to sign a petition opposing the Muslim travel ban, and we hope our film will encourage others to follow the Supreme Court case closely.

These events should be setting off alarm bells not only for the Japanese Americans who know about the incarceration but for all Americans who care about the Constitution and the civil liberties and civil rights that it guarantees. We are most likely on the verge of seeing the Supreme Court grant extraordinary powers to the Trump Administration in the name of national security and we need to be prepared to raise our voices in opposition to such a ruling.

What can those of us who aren’t targeted do to not be bystanders doing nothing? How do we support our neighbors?

Ginzberg: There is a good website that allies have set up called www.stoprepeatinghistory.org. The site contains links to the oral arguments in Trump v. Hawaii, the travel ban case.

The first step in any struggle like this is to educate yourself and your community and the film, And Then They Came for Us, provides an important look at what the US government did to over 110,000 Japanese Americans. Looking at the history of racism that underlay the incarceration has strong resonance today.

As Zahra Billoo says, "Camps don't happen overnight." It is a process that involves slow targeting and propaganda to isolate the group from the mainstream, then they make you register and then in the case of the Japanese Americans gave people 24-48 hours to leave their homes, businesses, pets and belongings behind. People did not speak up for the Japanese Americans or against the incarceration.

Today we must make our collective voices heard as we did at airports across the country when the travel ban was first announced. It will be up to all of us to see that the United States does not violate the US Constitution in the name of national security for the second time in a century.

Can you tell us a little bit about how your film is being used in communities who want to be inclusive and safe for everyone?

Ginzberg: We are making the film available to people across the country and many communities have put on their own screenings of the film at churches, local organizations and at theaters. We have a study guide that can be downloaded form the website and we have free copies available for public high schools that would like to screen the film. We also have posters that can be adapted for community screenings. Please visit our website to see these resources, thentheycamedoc.com. The film is available for personal/home use for $20 from the website.

Non-profit organizations and colleges can purchase the film from Good Docs: https://www.gooddocs.net/and-then-they-came-for-us

We hope people will consider purchasing a copy of the film for personal use and then encourage your public library or school to consider hosting a screening. We are happy to work with groups who are interested in putting on a community screening.