"Sshh, the University of Mississippi is being integrated," they said, and I remember glancing at the television set and seeing mean faces. I remember very, very angry people, and I simply remember saying to myself, "I would never go to a place like that.”

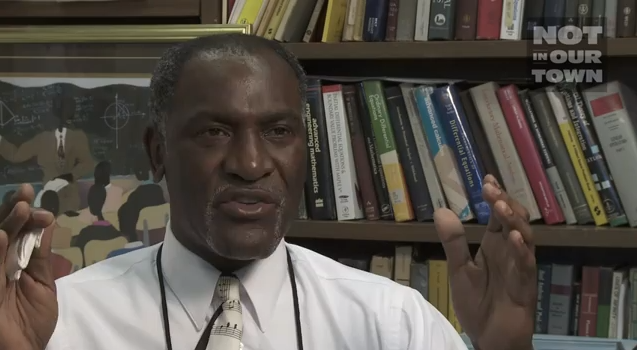

—Dr. Donald Cole, Assistant Provost, University of Mississippi, on learning about the integration of the university in 1962.

Here is an extended transcript of Not In Our Town's interview with Dr. Donald Cole, Assistant Provost, University of Mississippi. Watch snippets of this interview in the Class Actions web extra, "Dr. Cole: Ole Miss Legacy."

Where were you when James Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi in 1962?

I was in 6th grade and I just remember coming in the house and seeing my parents staring at the television set very intensely and I asked, What are you looking at? "Sshh, the University of Mississippi is being integrated," they said, and I remember glancing at the television set and seeing mean faces. I remember very, very angry people, and I simply remember saying to myself, "I would never go to a place like that.”

In 1968, you were one of a hundred African-American students who attended Ole Miss, what was that like?

The African American students would find comfort in one another. The guys would see the girls safely to class. But I also remember the way that the white males would tell me that I wasn't welcome at the university -- they would stand on the sidewalk and make me walk around them.

What was real, real interesting was a couple of the ways that the females would say that you're not welcomed here -- they would physically challenge me, there was a gesture (waves hand) and I didn't understand it, but I did notice that they were waving something and so when I looked a little closely, they were waving a rebel flag and so that was a way of them protesting our presence here without saying a word.

In reality, that was probably my real first encounter with the rebel flag. I knew it existed but I really never thought much of it, and it sort of became a symbol for me that made a statement that I wasn't welcome, made a statement that they didn't like me. So even though I didn't know what that meant I knew that I couldn't ask the white girls for a date for sure (laughs).

You were expelled two years later, why?

It wasn't long before I found out the place was not as comfortable as I wanted it to be and so we began to organize and to ask the administration that they do something to change the university so it would be a little more comfortable. What we were asking for, which I don't think was anything extraordinary, was to have black professors and black athletes, to see the university move in that direction. When we would go to the football games we would be taunted, and so we asked for a disassociation with the rebel flag. So what we were asking for we thought was reasonable, civil rights.

Of course the whole country was protesting at that time. People were protesting the Vietnam war and civil rights and everything and so we began to ask. And then our asking went to demands and then our demands went to protesting and so as a result of one particular protest that happened on this campus the authorities arrested close to 90 people, which, well, most African-Americans and which meant that it was nearly 90-plus percent of the African-Americans on campus so a big statement was being made.

We were aware that what we were doing could have been somewhat dangerous, we knew that citizens had been killed at other places as well for doing something similar, but as a result of that particular protesting event, eight of us were expelled from the university and I was among those eight people.

You returned to Ole Miss as a graduate student and later as a math professor, was it difficult to come back?

It wasn't difficult for me at all to come back during any of those times it was, I never hated the university. There were a couple of actions taken that I probably hated, a couple of individuals whose actions I probably hated as well, but the university itself I've loved and I've always loved. And I found it then very easy to serve and I find it today very easy to serve and naturally because of the length of time that I have been associated with the university I have seen a lot of things change.

And I always measure it both ways, as the glass being half empty and the glass being half full. The half empty part if relative to the fact that it needs more changing, so much more needs to be done. The half full part is appreciative of that which has changed.

When did you first hear Ole Miss students chanting, “The South Will Rise Again?”

We were at a football game where everyone is cheering and the spirits are fairly high and these words began to echo. So what's the meaning of those words? How do I interpret those words? How do I feel about those particular words, 'The South shall rise again'?

I'm a Southerner, Daddy was a Southerner, my Granddaddy, etc. and of course the South in its heyday had individuals likened to me in slavery type of conditions. And even when the slavery type of conditions passed, the South had people like me in a very inferior and second class citizenship type of position.

Well, that's my history of the South when it was quote, "on top," that's all that I and my family know about the South in its heyday. So 'the South shall rise again.' how am I to interpret that? For me, it means if you will, that racially I should be 'put in my place' it means for me racially that my children should not have opportunities as guaranteed by the country. For me here, it means a second class citizenship and reverting back to that and that's what it means to me and I can give it no other interpretation.

Did Chancellor Jones ask for your advice on how to handle the situation?

I’m sure that Dr. Jones knew what I was going to say. He probably asked my advice so that others could hear and not as much himself because he is a very progressive chancellor and I just love working with him and I love his thought processes if you will.

So as I recall when he asked me about some of this symbols, one of the things that he asked me is how do you justify something, taking away something from individuals, or the sense of it was, how can we justify banning this song or banning a number of other symbols associated with the university that some of the people would like? That would be taking something away from them.

And my response to that was that these things have a place in the history books, they have a place in the museums, but they don't have a place at the head of a progressive university that is representing all people that are served by that institution. And so my opinion was that let's put these symbols in the place where they belong, all can go to a museum and see these any time that they get ready. But for it to represent a university and the constituents of the university, all of who don't agree with that. it's not a place for that.

Were you surprised by the reaction to banning the football fight song and the chant?

I certainly thought that was the right thing to do and I think it was probably my thinking and everybody else that it would be a couple of people that were going to be dissatisfied for that and so we watched the opinion polls in the paper. But very quickly it began to dominate his schedule, it began to dominate his time, it began to dominate others' as well, so all of a sudden calls were coming in that had to be answered and a flood of controversial literature was being produced, hate mail if you will, a number of calls were coming in and so the outpouring of this was a little surprising to us.

Of course here we have a new chancellor and it was his job, as he said, to listen for a while. As he said, he was in the position where he was listening for a number of months, but this was not one for which he could continue to listen, he had to make some type of a statement and he did but the reaction to it, I think, kind of surprised all of us.

I think we all knew eventually of the outcome and perhaps that's why the reaction was so great. I really hadn't thought about it, perhaps it was the evil and mean-spirited individuals perhaps this was the last stand, perhaps it was now or never and so maybe that's why it got to be such a fury around campus. But nonetheless, it's not the fury that drives you, it's the moral intent of your heart.

When the Ku Klux Klan protested on campus, were you concerned that tensions would escalate?

I knew that the message that the KKK was delivering would not be well received by the majority of the individuals on the campus of the University of Mississippi. I knew that in a real sense that it was going to help that the KKK's message of wanting to keep Dixie and “The South shall rise again” and the banning of that, I knew that it would help our cause in getting rid of it because it would force some people to either stand up with them or to deny them. And that was perhaps the only solace that I found with them being on campus, that a turning point is being forced and it is but one way to go in this turning point.

How important is the student group One Mississippi?

One Mississippi is a group that I applaud. I think the student movement can be the most powerful movement on campus and I think that the power of students outweighs the power of any other entity on campus.

One Mississippi, when they are functioning at the optimum level, their voices can be heard over those of the chancellor, over those of the faculty, over those of anyone else, and so it's probably in this context that I just love that that particular group has come to raise a dialogue amongst other students and anyone else involved concerning race relations and racial progress here at the University of Mississippi and beyond.

How did Chancellor Jones handle this challenge?

I think that the history books will write this event and many others liken unto it will write it up in a way that makes our current Chancellor seem very progressive for his time then and very progressive for the time to come. And so it's incumbent upon us to take a stance for the people and to take a good moral stance and that’s why we are put into these positions.

I remember telling the chancellor almost apologizing, "Well, I'm sorry you have to be the one, but you're chosen for this, this is your legacy, this is your time. What I can do to help, I wish it could all be put on me, I wish I could all do it myself, and leave you clear. But for now you've taken a stand, you've taken the right moral stand. You're going to have to continue to do this and it's not going to be popular." And I just remember his response was, "Thank You Don."

Learn more about University of Mississippi's efforts to create an inclusive environment for all at niot.org/ClassActions.

Project:

Local Lessons:

Comments

Home State-Town

I do not have to read this story because Everything Dr. Cole is saying is true. Oxford is my home town and I was witness to many of the issues he's talking about. I am a friend of Dr. Cole as he was a friend and tutor in math at one point.

I'm glad he was able to share this story, because I have been trying to share my story which is more of the same, but I do not have an important status.

I moved away from Oxford Mississippi because of the racial acts against blacks still was very present in 2003. But, little than I knew, when I moved to Iowa, I found out that race relations with blacks and whites are just as bad in the mid-west.

I have storys of my own to share.

Thanks,

David L. Campbell, II

davidcampbell374@gmail.com